… for when he touched earth so it was that he waxed stronger, wherefore some said that he was a son of Earth.

– Apollodorus, Library, 1-2 A.D.

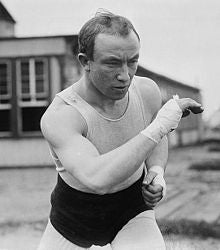

After his retirement from boxing in 1914, former bantamweight champion of the world Johnny Coulon (5 ft, 110 lbs) hit the vaudeville circuit demonstrating his apparently mysterious power to resist being lifted into the air.

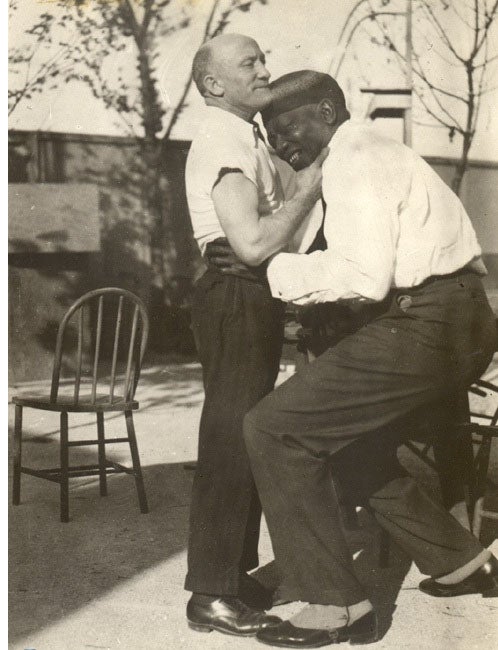

The act was simple; the tiny Coulon would first allow himself to be lifted by his “opponent”, typically a big heavyweight boxer, wrestler or weightlifter. The opponent would initially have no difficulty at all hoisting the smaller man into the air, especially as Coulon would tense his body into a straight vertical line and bear down upon the lifter’s wrists, effectively assisting in the lift.

Coulon would then apply his special counter-grip, in which he lightly seized the would-be lifter’s right wrist (over the pulse-point) with his left hand and placed his right index finger on the left side of the lifter’s neck, near the carotid artery. The results were always the same; regardless of how much he strained and struggled, the lifter couldn’t budge Coulon from the floor.

Here’s the only known newsreel film footage of Johnny Coulon in action, dating to 1921:

In 1920, after refining the act by touring American music halls and saloons, Coulon departed for Paris where his apparently “occult” abilities attracted a great deal of media attention. This was the height of the post-Great War Spiritualism craze; a time of peak popularity for seance sittings and interest in the “world beyond”. While Coulon was wowing Parisians with his seemingly mysterious ability, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was making international headlines promoting a set of photographs purporting to show two English schoolgirls playing with real fairies.

In this rarified environment, Johnny Coulon’s act was reportedly closely scrutinized by committees of physiologists, psychiatrists and other specialists led by Professor Charles Nordmann, who ran a battery of tests including wetting the tips of Coulon’s fingers and having him stand with his toes elevated on a small board, to change his center of gravity.

The committee concluded that a mysterious combination of physiological and psychological forces were at work, “not in the nature of an electric current and not in the nature of any force known to physiologists”:

In the dark wall which, till now, has resisted all attacks of experiment, the enthralling mystery of the relation of body and soul, of mental and material force, the phenomenon discovered by Johnny Coulon is perhaps the decisive breach through which science may perhaps soon enter to victorious attack.

Naturally, many people felt compelled to try to duplicate Coulon’s abilities, and it was reported that, for a time, no work was getting done in Paris because the smallest staffers at every office were being press-ganged into “Coulon lift” experiments.

When approached for comment by journalists, escapologist and arch-skeptic Harry Houdini replied:

It’s hokum! It’s the principle of the fulcrum and a matter of leverage. Coulon is in stable equilibrium and his subject isn’t. Coulon keeps his subject at arms’ length to get the best advantage of the leverage. Furthermore, the trick has been played before!

Houdini was referring to the “Georgia Magnet” act, which had, in fact, been a very popular vaudeville attraction dating back to the 1880s, but which had apparently been largely forgotten by the second decade of the 20th century. During the act’s late-Victorian heyday, several young women had enjoyed successful showbiz careers employing similar tricks of leverage and misdirection to create the illusion of superhuman powers.

As it happened, however, although Johnny Coulon never publicly explained his methods, Houdini was only partly correct in attributing the “Coulon effect” strictly to leverage.

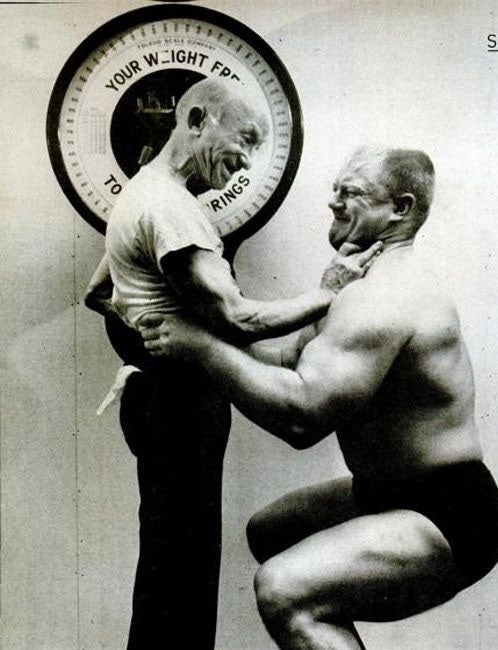

It’s likely that the scientific committee and other observers had been misdirected by the notion of “occult energy”, and perhaps also by the position of Coulon’s left hand on the lifter’s “pulse point”, into overlooking the fact that Coulon’s right forefinger pressed firmly into his opponent’s sensitive vagus nerve at the moment of the attempted lift. Simultaneously, Coulon’s right elbow was effectively aligned with his own right hip.

This pressure exerted a force of counter-leverage – invisible to the eye and probably not even noticed by the would-be lifter in the midst of his exertions – which effectively put the lifter in an impossible position. The greater their exertion, the stronger the counter-leverage via Coulon’s skeletal alignment and the greater the painful pressure against the lifter’s vagus nerve – a sensitive pressure point, regardless of size and muscular strength.

Experiments demonstrate that the left-handed “pulse point” grip was largely a matter of misdirection and showmanship; the liftee’s left hand can be limp at their side and the lifter still won’t be able to hoist them, as long as the liftee’s right hand and arm are properly aligned.

Even an exceptionally strong and aggressive lifter, who might be able to “fight through” the painful nerve pressure, would find Coulon impossible to raise due to the alignment of his elbow and hip. Extreme force would simply lever Coulon’s upper body slightly backward over his own center of gravity, breaking the optimal vertical line alignment and making him even harder to lift.

Thus, by setting the rules of the “test”, Coulon was able to combine an insurmountable leverage advantage with a painful disincentive to being lifted.

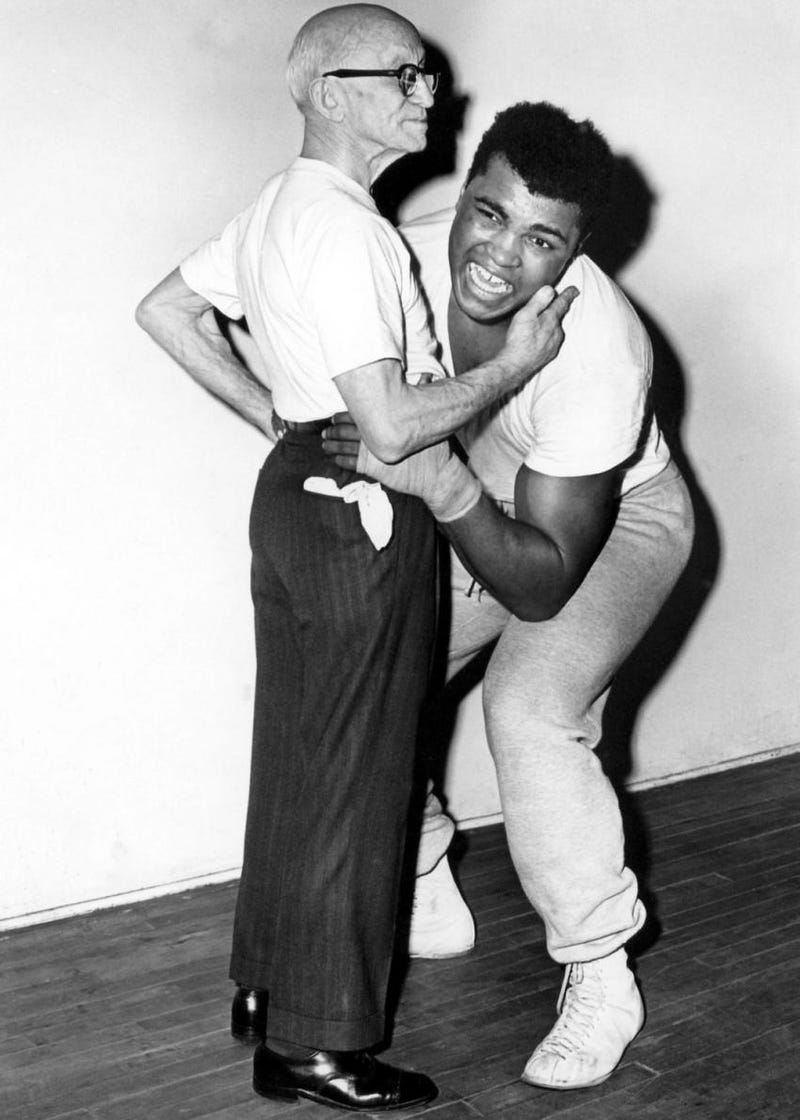

The general public eventually tired of the novelty and Coulon retired from show business, opening a successful Chicago gymnasium. For many decades thereafter, he would challenge visiting heavyweights including boxers Muhammad Ali and Jack Johnson to lift him into the air, and no-one ever managed the trick.

Johnny Coulon, the Unliftable Man, died at the age of 84 years on October 29, 1973.

Note: an earlier version of the above article originally appeared on the Past Tense blog during November of 2014. The updated article is published here by permission of the author.