The history of shadowy pop-fiction vigilantes is … well … shadowy, and answering the question “who was first?” requires some careful caveats.

This article is specifically an attempt to trace the lineage of those quasi/proto-superheroes who are literally masked and who assume a supernaturally-themed alternate identity to “strike fear into the hearts of evildoers”. Many of them are also aristocrats in their “everyday” lives. Therefore, I’m discounting the very long tradition of culture heroes (Gilgamesh, Hercules, Beowulf, et al), super-powered or otherwise, who don’t bother with actual secret identities in the comic book sense.

Robin Hood comes very close to being the trope originator, but I’d argue that he didn’t maintain a dual identity so much as simply adopt a new name (and, obviously, lifestyle); likewise, his motif was more “altruistic outlaw” than “supernatural avenger”.

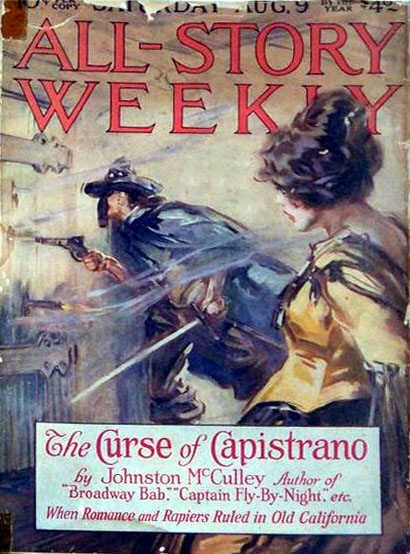

It’s commonly accepted that the masked avenger trope popularized in comic books during the 1940s was directly inspired by ’30s pulp fiction “mystery men” such as the Lone Ranger, the Shadow and the Phantom, with occasional glances further back to Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel (circa 1904) – who is discounted here because, although an expert in disguise, he did not have a distinctive, masked alter ego. Johnston McCulley’s Zorro, who premiered in The Curse of Capistrano (1919), certainly does qualify, and he is often justly cited as a direct precursor of the masked, shadowy vigilante pulp heroes of the ’30s.

However, Zorro himself had at least two predecessors, relatively little-known today, who had also manifested the “supernatural avenger” mystique.

1915 saw the first appearance of British author Russell Thorndike’s character, Dr. Christopher Syn, alias the Scarecrow. Doctor Syn: A Tale of the Romney Marsh was set in the coastal English village of Dymchurch during the 18th century, at a time when the villagers could only sustain themselves through smuggling. Dr. Syn – who was formerly and secretly a feared pirate known as Captain Clegg, and currently the apparently meek and mild village parson – assumes a third identity, that of the masked, demonic Scarecrow, to protect his parishioners from the King’s Revenue Men.

The Scarecrow was an expert strategist, rider, fencer and marksman, whose intimidating mask, costume and shrieking laugh instilled fear into his enemies. His sidekick, Mr. Mipps, also assumed a secret identity (as the skull-masked Hellspite) and they were headquartered in a hidden barn on the outskirts of Dymchurch.

Thorndike wrote a series of subsequent novels – actually prequels to Doctor Syn – and the series was later adapted into several movies, including three classic Disney tele-films starring Patrick McGoohan as Dr. Syn/the Scarecrow:

Appearing decades even before the Scarecrow, however, the mysterious Spring Heeled Jack may very well be the actual originator of many “masked avenger” tropes.

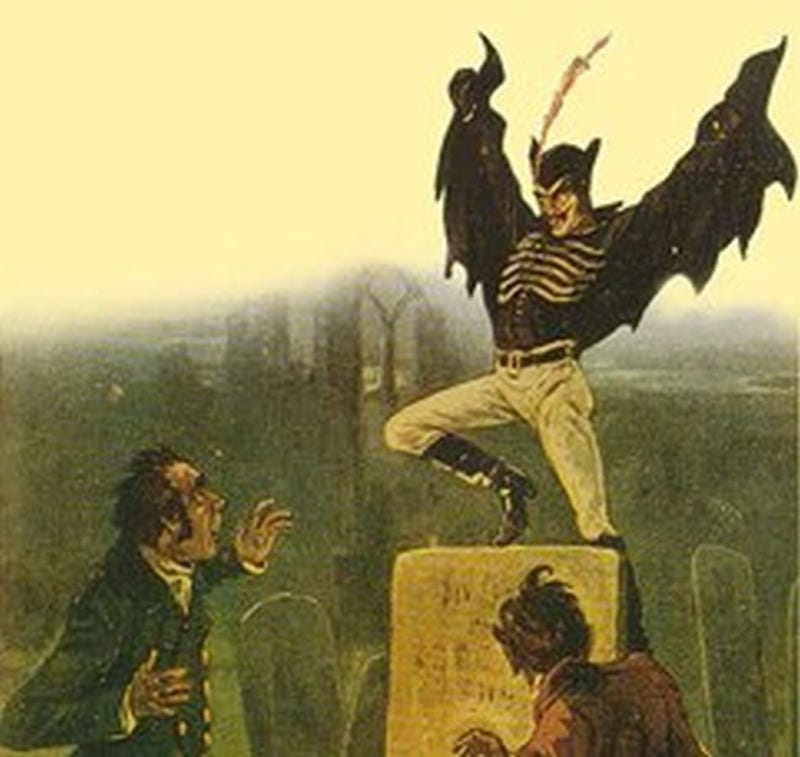

Stories of Spring Heeled Jack had first emerged during the 1830s. Confused London newspaper reports melded with rumor and gossip to conjure something approaching mass hysteria concerning this very strange figure, who was said to possess supernatural agility, to be able to spit blue and white flames and to be armed with steel claws. This early, folkloric rendition of Jack was an amorphous figure, sometimes said to be the devil in more-or-less human form; an acrobatic boogeyman who seemed to delight in leaping out from the shadows and molesting young women.

There is no doubt that Spring Heeled Jack became the most famous exemplar of the curious 19th century “playing the ghost” or “ghost act” craze, which was widely reported upon in newspapers at the time. “Ghost actors”, according to these reports, would dress in outlandish costumes and, thus disguised, would startle or even assault passers-by before vanishing back into the night (or, occasionally, being shot or beaten by their would-be victims).

Over a number of decades, though, actual (fearful) belief in Spring Heeled Jack gave way to nostalgia and whimsy. By the mid-19th century he was being featured as a villain in novels and plays, including a famous production mounted by the acrobat/actor/impresario George Conquest.

By the 1880s Jack was beginning to be portrayed as an anti-hero – though often drawn and described as resembling a monstrous man/bat/lion hybrid, springing about the streets and rooftops of London. It then required only a short leap (!) of the imagination to transform him into an outright hero.

Several circa 1900 “penny dreadful” iterations of Spring Heeled Jack, including many stories written by Alfred Burrage under the pseudonym “Charlton Lea”, portrayed Jack as a nobleman who had been cheated out of his inheritance and who took up a devilish disguise to punish those responsible. Along the way, Spring Heeled Jack also rescued damsels in distress and generally stood up for the innocent and downtrodden while terrifying evildoers. He wore a distinctive costume and was capable of performing incredible leaps thanks to a special pair of boots, credited in one tale to a secret mechanism invented by Indian street magicians.

Anticipating Zorro, Spring Heeled Jack was fond of marking both enemies and territory by carving his initial “S” with the point of his rapier. He also maintained a secret underground lair (in a converted crypt) and frightened his adversaries with his ringing laugh and catch-phrase, “The day is yours – leave the night to me!”.

Thus, it may be that, by fully transforming Spring Heeled Jack from an urban ghost story to a heroic “dark avenger”, penny dreadful author Alfred Burrage originated a number of narrative motifs and tropes that influenced subsequent generations of masked, supernaturally-themed vigilantes. By the time comic book heroes such as Batman were created, those motifs had already been further elaborated in pulp novels – most famously by Johnston McCulley’s Zorro character and by Russell Thorndike’s Scarecrow stories – and also in movie serials, to the point that they were part of the pop-literature zeitgeist.

If you can think of an earlier example of this trope, please let us know in the comments!

Note – an earlier version of the above article originally appeared on the Past Tense blog during October of 2014. It is re-used here by permission.