Believed to be the only filmed interview with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, this Fox Movietone newsreel item was given wide release during 1929.

Author: ‽

Jekyll and Hyde, Episodes 6 and 7- a Spring Heeled Jack-Oriented Review

ITV’s Jekyll and Hyde series (2015) somewhat updates and definitely expands upon the themes of the classic story, being set in London and Ceylon during the 1930s. Tom Bateman plays Dr. Robert Jekyll, a grandson of Dr. Henry Jekyll. Robert has inherited his grandfather’s dark, superhuman alter-ego and, a la Bruce Banner, is inclined to transform into Hyde during times of great stress.

The series embroils Jekyll/Hyde in an ongoing “secret war” between two rival forces; the MIO (Military Intelligence: Other), a branch of Her Majesty’s Secret Service dedicated to hunting supernatural menaces, and Tenebrae, an order of occultists with a sinister agenda.

This review, however, concentrates on Jekyll and Hyde‘s Spring Heeled Jack storyline, which is spread across Episodes 6 and 7. This is of special interest because it represents the first time this storied figure of folklore has been prominently featured in a television series.

Having admitted that bias:

Episode 6 begins promisingly as Spring Heeled Jack appears, in all his hissing, steampunk/plague doctor glory, on the shadowy rooftops of London:

… before plunging down into the dark, only to re-appear a moment later, off in the distance, bounding or even flying along the roofscape by means of some sort of jet-propulsion. This is the image of Spring Heeled Jack that long-term fans have been waiting to see on series TV and it’s very satisfying.

’30s Londoners, of course, are shocked to learn that this Victorian ghost/demon has returned to haunt them, and are thrown into an actual panic when bodies begin showing up in the back alleys, seemingly eaten from the inside and missing vital organs. Jekyll/Hyde are both on the case for their own reasons, Robert Jekyll bringing his measured temperament and medical expertise to bear while Hyde employs more primitive means.

T(he)y do, in fact, track down the mysterious Spring Heeled Jack, and here the storyline, unfortunately, starts to disappoint SHJ fans. After being easily defeated and embarrasingly put on display by Hyde, SHJ is unmasked as a young engineer’s apprentice named Burton. The lad’s motivations are honourable; he is the grandson of the original Spring Heeled Jack, who was also an altruistic “monster hunter”, and Burton has been moved to bring grand-dad’s pseudonym and flying suit out of moth-balls to investigate the recent rash of organ-stealing.

Burton proposes to team up with Hyde in catching whatever monster is really to blame, but the characters have no chemistry and Burton proves to be of mediocre actual use in a crisis; he’s just a well-meaning, rather hapless young chap in a cool suit. The real villain, as it turns out, is Kephri, a supernatural insectoid parasite able to inject humans with centipede-like larvae that can control the victim’s behaviour.

No sooner do the heroes realise this fact than poor Burton is jabbed by Kephri and flies off, now under the demon’s spell; roll credits.

Episode 7 picks up some short time later, as a cheeky young newsboy who has just assured everyone that “there are no monsters” is instantly yanked into the sky by (we assume) Spring Heeled Jack doing Kephri’s bidding. Robert Jekyll and his brother Ravi investigate the scene and discover the victim’s dessicated husk on a nearby rooftop, along with the unconscious Burton, still wearing his Spring Heeled Jack outfit but now shrouded in a coccoon-like mass of silken threads.

Returning Burton to his laboratory, Robert swears to try to get rid of the monster within him, but before he can really help, Spring Heeled Jack re-awakens and escapes back to the rooftop, only to be shot dead by MIO agents moments later.

So; we’re just over ten minutes into Episode 7, and they’ve killed off Spring Heeled Jack, whose entire contribution to the storyline has been one cool rooftop appearance, losing a short “fight” with Hyde, being humiliated and exposed as a callow youth in grand-dad’s superhero suit and then falling under the control of a demonic grasshopper. It’s as if the writer realised he disliked the character, or was worried that he’d steal Jekyll/Hyde’s thunder; SHJ’s arc certainly suffers badly in comparison, plummeting from mysterioso rooftop badass to hapless sidekick to pawn to corpse.

Now, obviously there may well be practical reasons for this treatment – it must be difficult to do justice to Spring Heeled Jack on a relatively low budget, especially if your version of the character can actually fly, given the expense of elaborate stunt sequences and special effects. It’s entirely possible that the writer did the best he could with what he had to work with. Still, for those who have been waiting a long time to see Jack featured on screen, this outing was a let-down.

Nice suit, though.

RATING(S):

‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ _ _ _ _ _ _

for Spring Heeled Jack fans

Only four ibangs out of ten for what comes across as a missed opportunity.

To be fair, the other elements of the show are passably entertaining, so if you’re not a Spring Heeled Jack fan, you may well enjoy it more than we did:

‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ _ _ _ _

for fans of ’30s-set fantasy/action/drama

The Secret Origins of the “Masked Avenger” Trope

The history of shadowy pop-fiction vigilantes is … well … shadowy, and answering the question “who was first?” requires some careful caveats.

This article is specifically an attempt to trace the lineage of those quasi/proto-superheroes who are literally masked and who assume a supernaturally-themed alternate identity to “strike fear into the hearts of evildoers”. Many of them are also aristocrats in their “everyday” lives. Therefore, I’m discounting the very long tradition of culture heroes (Gilgamesh, Hercules, Beowulf, et al), super-powered or otherwise, who don’t bother with actual secret identities in the comic book sense.

Robin Hood comes very close to being the trope originator, but I’d argue that he didn’t maintain a dual identity so much as simply adopt a new name (and, obviously, lifestyle); likewise, his motif was more “altruistic outlaw” than “supernatural avenger”.

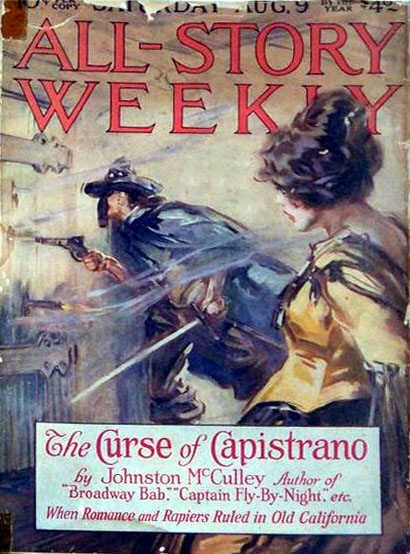

It’s commonly accepted that the masked avenger trope popularized in comic books during the 1940s was directly inspired by ’30s pulp fiction “mystery men” such as the Lone Ranger, the Shadow and the Phantom, with occasional glances further back to Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel (circa 1904) – who is discounted here because, although an expert in disguise, he did not have a distinctive, masked alter ego. Johnston McCulley’s Zorro, who premiered in The Curse of Capistrano (1919), certainly does qualify, and he is often justly cited as a direct precursor of the masked, shadowy vigilante pulp heroes of the ’30s.

However, Zorro himself had at least two predecessors, relatively little-known today, who had also manifested the “supernatural avenger” mystique.

1915 saw the first appearance of British author Russell Thorndike’s character, Dr. Christopher Syn, alias the Scarecrow. Doctor Syn: A Tale of the Romney Marsh was set in the coastal English village of Dymchurch during the 18th century, at a time when the villagers could only sustain themselves through smuggling. Dr. Syn – who was formerly and secretly a feared pirate known as Captain Clegg, and currently the apparently meek and mild village parson – assumes a third identity, that of the masked, demonic Scarecrow, to protect his parishioners from the King’s Revenue Men.

The Scarecrow was an expert strategist, rider, fencer and marksman, whose intimidating mask, costume and shrieking laugh instilled fear into his enemies. His sidekick, Mr. Mipps, also assumed a secret identity (as the skull-masked Hellspite) and they were headquartered in a hidden barn on the outskirts of Dymchurch.

Thorndike wrote a series of subsequent novels – actually prequels to Doctor Syn – and the series was later adapted into several movies, including three classic Disney tele-films starring Patrick McGoohan as Dr. Syn/the Scarecrow:

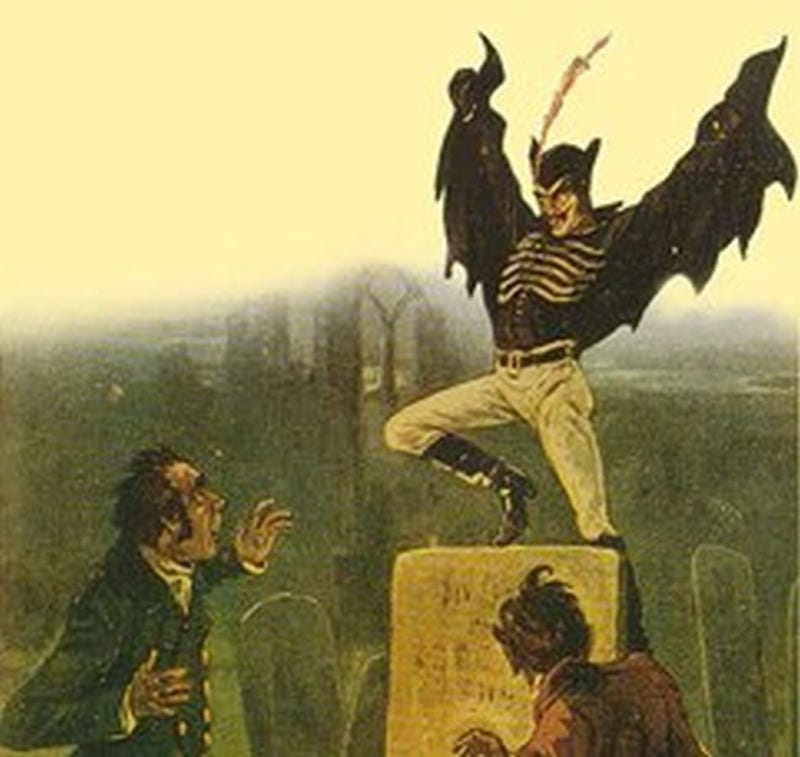

Appearing decades even before the Scarecrow, however, the mysterious Spring Heeled Jack may very well be the actual originator of many “masked avenger” tropes.

Stories of Spring Heeled Jack had first emerged during the 1830s. Confused London newspaper reports melded with rumor and gossip to conjure something approaching mass hysteria concerning this very strange figure, who was said to possess supernatural agility, to be able to spit blue and white flames and to be armed with steel claws. This early, folkloric rendition of Jack was an amorphous figure, sometimes said to be the devil in more-or-less human form; an acrobatic boogeyman who seemed to delight in leaping out from the shadows and molesting young women.

There is no doubt that Spring Heeled Jack became the most famous exemplar of the curious 19th century “playing the ghost” or “ghost act” craze, which was widely reported upon in newspapers at the time. “Ghost actors”, according to these reports, would dress in outlandish costumes and, thus disguised, would startle or even assault passers-by before vanishing back into the night (or, occasionally, being shot or beaten by their would-be victims).

Over a number of decades, though, actual (fearful) belief in Spring Heeled Jack gave way to nostalgia and whimsy. By the mid-19th century he was being featured as a villain in novels and plays, including a famous production mounted by the acrobat/actor/impresario George Conquest.

By the 1880s Jack was beginning to be portrayed as an anti-hero – though often drawn and described as resembling a monstrous man/bat/lion hybrid, springing about the streets and rooftops of London. It then required only a short leap (!) of the imagination to transform him into an outright hero.

Several circa 1900 “penny dreadful” iterations of Spring Heeled Jack, including many stories written by Alfred Burrage under the pseudonym “Charlton Lea”, portrayed Jack as a nobleman who had been cheated out of his inheritance and who took up a devilish disguise to punish those responsible. Along the way, Spring Heeled Jack also rescued damsels in distress and generally stood up for the innocent and downtrodden while terrifying evildoers. He wore a distinctive costume and was capable of performing incredible leaps thanks to a special pair of boots, credited in one tale to a secret mechanism invented by Indian street magicians.

Anticipating Zorro, Spring Heeled Jack was fond of marking both enemies and territory by carving his initial “S” with the point of his rapier. He also maintained a secret underground lair (in a converted crypt) and frightened his adversaries with his ringing laugh and catch-phrase, “The day is yours – leave the night to me!”.

Thus, it may be that, by fully transforming Spring Heeled Jack from an urban ghost story to a heroic “dark avenger”, penny dreadful author Alfred Burrage originated a number of narrative motifs and tropes that influenced subsequent generations of masked, supernaturally-themed vigilantes. By the time comic book heroes such as Batman were created, those motifs had already been further elaborated in pulp novels – most famously by Johnston McCulley’s Zorro character and by Russell Thorndike’s Scarecrow stories – and also in movie serials, to the point that they were part of the pop-literature zeitgeist.

If you can think of an earlier example of this trope, please let us know in the comments!

Note – an earlier version of the above article originally appeared on the Past Tense blog during October of 2014. It is re-used here by permission.

Houdini and Doyle, Episode 3: In Manus Dei (reviewed)

Edwardian-social-issue-of-the-week: faith healing

“Supernatural” crime: faith … killing (?)

We open inside a traveling tent-show where faith healer Elias Downey is explaining the origin of his miraculous powers to an enraptured audience. God, we are told, used Elias as a conduit in healing his desperately ill younger sister, Jane, when the Downeys were both children. A skeptic scoffingly interrupts and, shortly thereafter, falls to the floor, coughing blood and insensible. His wife desperately pleads with Elias to save him, but it’s too late – the man is dead.

Houdini, Doyle and Stratton attend the dead man’s funeral, hoping to gather enough evidence to prove that a crime has actually been committed, in order to be able to order an autopsy. Elias Downey arrives to pay his respects and Houdini (sacrificing all decorum for expedience) baits him into a loud science vs. faith confrontation, distracting the mourners while his colleagues examine the corpse. Doyle deduces that the man may have been suffering from dengue fever, and may therefore have died of natural causes after all.

Constable Stratton, however, discovers that several other people have died shortly after disparaging Reverend Downey and the team then attends another of his faith healing services. Houdini performs an impromptu demonstration of “psychic surgery” on a member of Downey’s audience, to illustrate the power of the placebo effect; the man is deceived by the trick and believes himself to be cured, and so he feels better. Ironically, Houdini himself then falls violently ill; meanwhile, Doyle is convinced of Reverend Downey’s powers and asks him to try to heal his comatose wife, Touie, who does, in fact, rally shortly after Downey prays over her.

Doyle, doubting his earlier diagnosis of dengue fever, conducts an illicit autopsy on the dead skeptic and is overcome by a toxic miasma rising from the man’s incised abdomen; coming to, he realises that the man was poisoned, suggesting foul play in the other deaths that have befallen people who scoffed at Downey. While Doyle and Stratton interview the wife of the dead skeptic, Houdini performs his matinee magic show, but is again overcome by illness and fails to escape the Water Torture Cell, requiring a dramatic glass-smashing rescue.

Eventually it transpires that the Reverend’s sister, Jane, has been bumping off “disbelievers” in order to bolster her innocent brother’s reputation, and thus his ability to do some actual good, even if only via the placebo effect.

The main emotional through-line in this episode lies in Arthur’s relationship with his newly-revived wife Touie. As the story began, he was losing hope that she would recover and was packing her clothes away in storage. After she regains consciousness (as it turns out, she was actually healed by an experimental medical treatment rather than by the Reverend’s prayers), the two of them share some tender moments … but tragically, by episode’s end she has relapsed into the coma. The distraught Doyle is comforted by his young daughter, and then, together, they unpack Touie’s clothing and re-hang it in her closet.

Observations:

- We’re asked to accept a lot of coincidences in this episode, especially regarding the timing of various illnesses and recoveries, which fit so neatly and dramatically into the storyline as to severely strain credibility.

- Episode 3 is basically an examination of both the limited and erratic benefits and significant dangers of faith healing – here identified as nothing, more nor less, then the placebo effect, bolstered by the above-mentioned heavy dose of dramatic license. The ever-skeptical Houdini offers some trenchant and accurate observations along these lines, and while the more credulous Doyle is always ready to accept a supernatural explanation, his practical skills as a physician are crucial to solving the case.

- Constable Stratton doesn’t have a great deal to do this time, other than to glance sternly at the two “boys” while they banter; hopefully she’ll have more of an active role in the rest of the season, aside from being Houdini’s burgeoning love interest.

RATING:

‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ _ _ _ _

Only six ibangs this week, but we’re looking forward to Episode 4, when Houdini and Doyle take on the legendary “leaping ghost”, Spring Heeled Jack!

“Here Be Dragons”: An Introduction to Critical Thinking

Written and presented by Brian Dunning, host and producer of the Skeptoid podcast and the author of the Skeptoid book series, Here Be Dragons is a great primer on critical thinking in evaluating pseudoscientific claims.