What if you met a slight young woman who claimed to be able to overpower the strongest men, due to her mastery of a supernatural energy?

During the late 19th century, several women not only made that claim, but also made a lot of money by demonstrating their “powers” in touring music hall and vaudeville acts …

Who was the “Georgia Magnet”?

“Annie May Abbott”, whose real name was Matilda Tatro, was one of the most successful of the “Georgia Magnet” or “Electric Girl” performers. The “Magnet act” had been touring music hall and vaudeville stages since 1883, when Lulu Hurst, the original Magnet, had first risen to prominence in the USA.

“Magnets” were typically slender young women who claimed to be able to manipulate a hitherto-unknown power, said to be akin to electricity or magnetism, that allowed them to perform superhuman feats of strength, under certain conditions. This description of a Magnet’s performance from a Minnesota newspaper dated October 15, 1890 is typical:

It was the most wonderful and utterly inexplicable exhibition – a genuine phenomenon – ever witnessed in this country. People may scoff and turn up their nose at the supernatural or, unnatural forces, if you please. Hypnotism until recently had but few believers. Mesmerism and kindred phenomena were thought to be high-flown titles for “fraud” and “fake,” but science has taken a hand and dispelled such ideas. It sounds a little “fishy” to state that she lifted two feet clear from the floor nine heavy men at one time, piled upon two heavy chairs, and as easily as the reader would this paper; in fact two gentlemen had their hands interposed between her hands and the chair, with no other contact when the entire mass came up, and those gentlemen assert that there was no more perceptible pressure against their hands than the weight of the hand.

Her muscles were examined during the tests and no sort of muscular action was found. What does it? The committee all tried singly to lift her, which the smallest man could do (she weighs not over 95) when she willed it, but when she preferred not, it remained not. Men tugged till their eyes bulged and they were red and blue in the face, but she remained smiling and as immovable as a block of buildings. Two, three four, six and eight men together expended all their strength in vain to hoist her a particle. She picked men up by the ears, by the head, hoisted them on poles, by her fingers tumbled them around like paper balls.

Many believers in the Magnet’s powers attributed them to the odic force, a mysterious energy that was held to be akin to electricity or magnetism. This force was also believed to animate the psychic phenomena associated with spiritualistic seances.

Barton-Wright meets the Magnet

By November of 1895, “Annie May Abbott’s” world tour had brought her to Japan. She and her manager, Richard N. Abbey – who had previously managed another Magnet, whose real name was Dixie Haygood – joined forces with a Professor Frank E. Wood, who served as their translator. They performed a series of shows, or “demonstrations”, at theatres throughout Japan, eventually arriving in the town of Kobe.

The Magnet’s act consisted of two main parts. First, manager Abbey would deliver a short lecture on the mysterious forces that were Miss Abbott’s to command, his speech translated for their largely Japanese audiences by Professor Wood. Then, a committee would be invited onto the stage in order to test these feats as the Magnet herself performed them. The committee was typically made up of volunteers from the audience, ideally large, strong men.

One of the committee volunteers in this case was E.W. Barton-Wright, an English entrepreneur and civil engineer who was both working and studying the martial art of jujitsu in Kobe at the time. The athletic Barton-Wright would have made a fine volunteer, also possessing the distinct advantage of speaking English, so that he would have no difficulty in following Mr. Abbey’s instructions during the “experiments” on stage.

After the show, the committee was required to sign a testimonial as to the Magnet’s success in the various feats performed on stage.

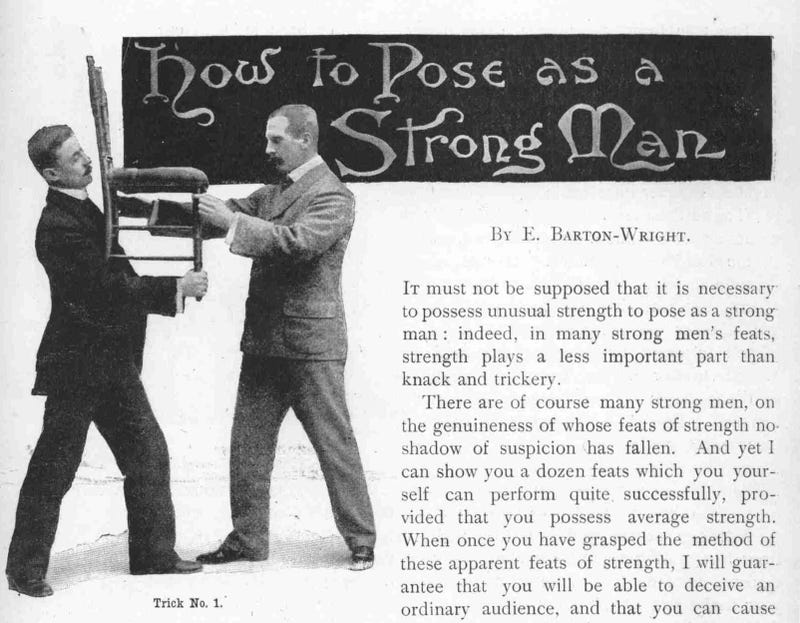

How to Pose as a Strong Man

E.W. Barton-Wright’s true impressions of the Magnet’s performance became clear several years later, when he authored a detailed expose of “Georgia Magnet”-type stunts. The illustrated essay “How to Pose as a Strong Man” was published in Pearson’s Magazine during January of 1899, and included the statements:

It must not be supposed that it is necessary to possess any unusual strength to pose as a strong man; indeed, in many strong men’s feats, strength plays a less important part than knack and trickery.

… (The Georgia Magnet) declared that it was solely owing to the fact that she possessed remarkable magnetic and electric powers that she was able to perform these feats. This, of course, was not the case, for anyone of average strength, who follows these instructions, will be able to perform them.

Armed with his intimate technical knowledge of “balance and leverage as applied to human anatomy”, which was to become a cornerstone of his Bartitsu martial art, Barton-Wright proceeded to explain how to perform numerous illusions of superhuman strength. He also addressed the psychological aspect of the Magnet’s act, referring to techniques of distracting the audience’s attention from the actual methods employed through “patter” and misdirection.

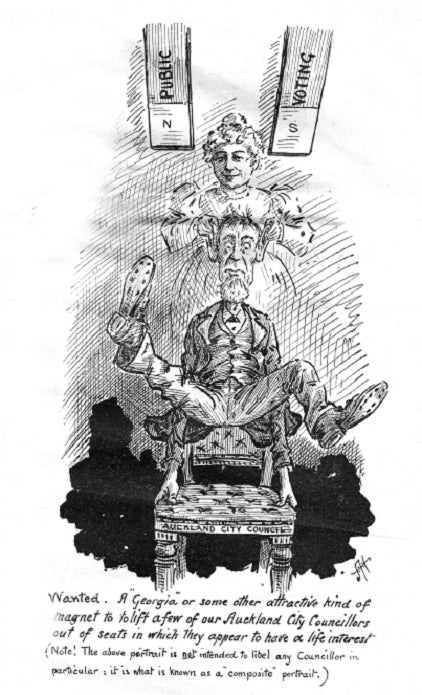

In fact, aspects of the Magnet act had been repeatedly exposed by academic skeptics in various newspaper and magazine articles dating back to the 1880s, but Barton-Wright’s concise essay, well-illustrated with step-by-step photographs, was unusually accessible to the lay-reader. Therefore, it was with some evident delight that the editor of the New Zealand Graphic newspaper decided to re-print “How to Pose as a Strong Man” during Annie May Abbott’s extended tour of New Zealand in 1899. In the same issue, the editor printed a satirical cartoon suggesting that the Magnet might use her powers to “lift” certain recalcitrant City Council members out of their seats.

Response from the Magnet’s representatives was swift and came in the form of a politely blistering letter to the editor of the Auckland Star, which was published on September 11th:

I shall be glad if you will allow me space to point out the essential differences between the feats set out in the article and the tests accomplished by Miss Abbott. As a preliminary, I may state that the article in “Pearson’s Magazine” was written by a Mr E. W. Barton-Wright, and was published as a sort of counterblast to a complimentary testimony to the “Georgia Magnet’s” ability, which appeared in the “Strand Magazine.” It must also be remembered that at this time the rival firms of Newnes and Pearson were sparing no effort to go one better than the other.

The above facts are well known, and only require being brought to mind, but it is not generally known that Mr. Barton-Wright attended one of Miss Abbott’s performances in Kobe, Japan, in November, 1895, and as a member of her committee signed his name to a testimonial almost similar to the one signed by the Auckland committee on Tuesday week. Perhaps he was “led by the nose” in the manner so elegantly suggested by Mr. Kent in a recent letter; but probably he signed the document of his own free will. In any case, the publication of his article in the “Graphic” Is calculated to throw discredit upon Miss Abbott, for it attempts to explain her feats as purely mechanical operations.

The Magnet’s defender in this instance was a man named Danvers Hamber, who was, at that time, the assistant editor of the New Zealand Sporting and Dramatic Review. In a high dudgeon, he proceeded to point out the various ways in which Miss Abbott’s performance differed from Barton-Wright’s descriptions, before finishing:

Mr. Barton-Wright undoubtedly used Miss Abbott’s performance as the foundation of his article. He forgot much in the three years which elapsed between witnessing Miss Abbott’s tests at Kobe and writing the paper. He probably forgot all about signing the testimonial to the lady’s ability, and he certainly let the truth slide in concocting many of the above little stories. His article may probably harm Miss Abbott’s tour through New Zealand. Here in Auckland we have already seen the effect it has upon the medical profession. If it can so disturb members of what is considered a calm and judicious calling, what may it not do with persons who have less control over their judgment?

There may well have been divergences between Barton-Wright’s descriptions and Miss Abbott’s demonstrations. Barton-Wright had addressed the fakery of “Georgia Magnet”-style feats in general rather than Annie May Abbott’s act in particular, and his article also included several feats that were not part of the standard Georgia Magnet repertoire. It would be interesting to read the exact wording of the testimonials signed by the various committees, there being a significant difference, for example, between the statements “I saw Miss Abbott resist the strength of several men” and “I saw Miss Abbott use odic force to resist the strength of several men.”

Moreover, as Barton-Wright had explained, there are several ways to perform the various Georgia Magnet “experiments” without resorting to “odic force”, all of them requiring the practiced application of leverage and balance combined with the ideomotor effect – the influence of imagination, suggestion and/or expectation on unconscious bodily movement. Specific to the Georgia Magnet “experiments”, subjects who believed that they would not be able to overcome the “odic force” tended to find that they could not, while those who believed that the force was stronger than they were tended to find themselves flung about the stage. These effects were exacerbated by the strict rules of the “tests”, which subtly disadvantaged the volunteers in terms of position, momentum and leverage.

The ideomotor effect was first formally described and defined by William Benjamin Carpenter during the mid-19th century. A physician and physiologist with a strong critical interest in claims of psychic phenomena, Carpenter observed and then proved that the apparently mysterious workings of spiritualistic phenomena including ouija boards, table turning and dowsing could easily be explained at the psychophysiological level.

Danvers Hamber’s fears were somewhat justified, as several other New Zealand newspapers followed the Graphic’s lead and printed skeptical editorials as the Magnet’s tour continued through the provinces. The consensus was that, while the show was very entertaining, the “odic force” patter was past its prime. The editor of the Timaru Post asserted that:

.. the “Georgia Magnet” possesses no power, psychic or otherwise, that is not possessed by every member of her sex. As an example. The “Georgia Magnet” holds the downward end of a stick in her clenched right hand, and one or two men are expected to force it through. Why, almost a child could resist their efforts. We know it is claimed that she does not grasp the stick, but we have seen her do it. Every one of her tricks is explainable in as simple a manner, even to the rising of her temperature and simultaneous lowering of her pulse, which seems to have puzzled the doctors so much. Of course, the temperature is raised by her exertions and the surrounding atmosphere, while a couple of minims of tincture of aconite does the rest, as far as the pulse is concerned.

Twice has the “Magnet” been lifted from the local platform, despite her exertions and anatomical distortions, and twice has it been clearly demonstrated that there has been no magnetism or “new force” holding her down, and the nonsense talked about “flesh contact” is as meaningless as it is void of truth.

As previously stated, we have no objection to such exhibitions as shows, merely; but we are bound to protect truth and science from incursions of that description. It is unlikely the Magnet will attract much more in New Zealand, as all the papers are busy exposing her tricks. We have had one “feat” explained to us, and see the impossibility of standing still while clasping a chair in both arms, even though the contrary force is exerted only by some one’s little finger.

It’s unlikely that E.W. Barton-Wright was even aware of the part played by his article in this controversy, but there’s no reason to doubt that it would have pleased him.

Note – an earlier version of the above article originally appeared on the Past Tense blog and on the Bartitsu Society website. It is re-used here by permission.

Supernatural mysteries form a significant subsection of the annals of detective fiction, and may or may not be considered to include that rarified class of stories in which an apparently supernatural mystery – an “impossible crime” – is revealed as being nothing of the sort. The progenitor of the “ghost-exposer” sub-genre may well be this series of short stories co-authored by

Supernatural mysteries form a significant subsection of the annals of detective fiction, and may or may not be considered to include that rarified class of stories in which an apparently supernatural mystery – an “impossible crime” – is revealed as being nothing of the sort. The progenitor of the “ghost-exposer” sub-genre may well be this series of short stories co-authored by