Jesus was sitting on a rock in the desert, meditating and reading the Law, when Tarzan came riding up on a goat. Tarzan was munching nutmeg seeds and playing the harmonica. “Hi, Jesus,” he yelled.

Jesus jumped like he was stung by a scorpion. “You startled me,” he stammered. “I thought at first you were Pan.”

Tarzan chuckled. “I can understand why that put you uptight. When you were born, the cry went through the wor1d, ‘Great Pan is dead.’ But as you can plainly see, I’m hairy all over like an ape. Pan was a shaggy beast from the waist down. Above his belly button he was a lot like you.”

A shudder vibrated Jesus’ emaciated frame. “Like me?” he asked. “No, you must be mistaken. Say, what’s that you’re eating?”

“Nutmeg seeds,” said Tarzan, grinning. “Here, I’ll lay some on you.”

“Oh, no thanks,” said Jesus. “I’m fasting.” Saliva welled up in his mouth. He pressed his lips together forcefully, but one solitary trickle broke over the flaky pink dam and dripped in an artless pattern into his beard. “Besides, nutmeg seeds; aren’t they a narcotic?”

“Well, they’ll make you high, if that’s what you mean. Why else do think I’m gumming them when I’ve got dates, doves and a crock of lamb stew in my saddle bag? If you ask me, you could use a little something to get you off.”

At the mention of lamb stew, Jesus had lost control of his lake of spittle. Now he wiped his chin with a dusty sleeve, embarrassment coloring his dark cheeks as the rosy-fingered dawn colors so many passages of Homer. “No, no,” he said emphatically. “John the Baptist turned me on with mandrake root once. It was a rewarding experience, but never again.” He shielded his eyes against the radiant memory of his visions. “Now, I’m what you might call naturally stoned.”

Tarzan, who had climbed off his goat, smiled and said, “Good for you.” He sat down beside Jesus and mouthed his harmonica. A jungle blues. “You gotta blow a C-vamp to get a G sound on one of these,” he said. He did it.

Obviously distracted, Jesus interrupted. “What did you mean when you said that Pan was a lot like me?”

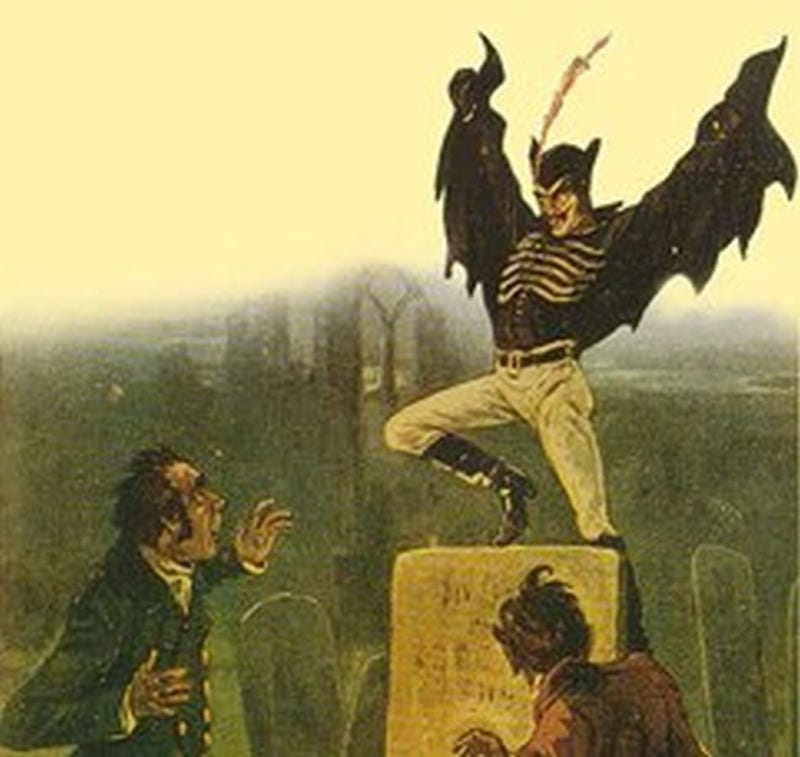

“Only from the waist up,” corrected Tarzan. “Above the waist Pan was a highly spiritual dude. He sang and played sweeter than the larks; and his face was as full of joy as a sunny meadow in spring. There was a lot of love in that crazy rascal, just as there’s a lot in you. Of course, he had horns, you know. And cloven hooves. Good golly, Miss Molly, how those woolly legs of his could dance! But he stunk, Pan did. In rutting season you could smell him a mile away. And he’d take on anything. He would’ve screwed this nanny goat if he couldn’t find a nymph.” Tarzan laughed and ran the scale on his harmonica.

Jesus didn’t appreciate the references to carnal knowledge. He made an attempt to get his mind back on the Law. But whenever his formidable intellect voyaged on the roiling sea of Hebrew instruction, it drew the image of Pan like a dory behind it.

Finally, he shoved Moses aside and asked, “But you say he was a lot like me.”

“I said that, didn’t I, man? I said he was like you, but different, too. Pan was the god of woodlands and pastures, the deity of flocks and shepherds. He was into a Wilderness thing but he was also into a music thing. He was half man and half animal. Always laughing at his own shaggy tail. Pan represented the union between nature and culture, between flesh and spirit. Union, man. That’s why we old-timers hated to see him go.”

The newsboys of paranoia hawked their guilty papers in Jesus’ eyes. They were the same shrill urchins who would be hawking when Jesus would predict his disciples’ betrayal and denial; when, in his next-to-last words, he would accuse God of forsaking him. “Are you blaming me?” he asked. His stare was as cold and nervous as a mousetrap.

By this time, Tarzan was pretty loaded. He didn’t want any unpleasantness. “All I know is what I read in the papers,” he said. He waved his harmonica to and fro so that it twinkled in the sunlight. “Do you have a favorite tune?”

“I like anything with soul in it,” Jesus replied. “But not now. Tell me, Tarzan, what did my birth have to do with Pan’s demise?”

“Jesus, old buddy, I’m not any Jewish intellectual and I can’t engage you in no fancy theological arguments such as you’re used to in the temples. But if you promise, Scout’s honor, not to come on to me with a thick discussion, I’ll tell you what I know.”

“You have my word,” said Jesus. He squinted in the agreed direction of Paradise, whereupon he noticed for the first time that an angel was hovering over them, executing lazy white loop-the-loops against the raw desert sky. “That angel will report everything it hears,” thought Jesus. “I’d better mind my P’s and Q’s.”

Tarzan spotted the angel, too, but paid it little attention. The last time he bad eaten nutmeg seeds he had seen a whole dovecote of them. One had landed on his head and pissed down his back.

“In the old days,” Tarzan began, “folks were more concrete. I mean they didn’t have much truck with abstractions and spiritualism. They knew that when a body decomposed, it made the crops grow. They could see with their own eyes that manure helped the plants along, too. And they didn’t need Adelle Davis to figure out that eating plants helped them grow and sustained their own lives. So they picked up that there were connective links between blood and shit and vegetation. Between animal and vegetable and man. When they sacrificed an animal to the corn crop, it was a concession to the obvious relation between death and fertility. What could be less mystical? Sure, it was hoked up with ceremony, but a little show biz is good for anyone’s morale. We were linked to vegetation. Nothing in the vegetable world succumbs. It simply drops away and then returns. Energy is never destroyed. We planted our dead the way we planted our seeds. After a period of rest, the energy of corpse or seed returned in one form or another. From death came more life. We loved the earth because of the joy and good times and peace of mind to be had in loving it. We didn’t have to be ‘saved’ from it. We never plotted escapes to Heaven. We weren’t afraid of death because we adhered to nature and its cycles. In nature we observed that death is an inseparable part of life. It was only when some men – the original tribes of Judah – quit tilling the soil and became alienated from vegetation cycles that they lost faith in the material resurrection of the body. They planted their dead bull or their dead ewe and they didn’t notice anything sprout from the grave; no new bull, no new sheep. So they became alarmed, forgot, the lesson of vegetation, and in desperation developed the concept of spiritual rebirth.

“The idea of a spiritual – invisible – being was the result of the new and unnatural fear of death. And, the idea of a Supreme Spiritual Being is the result of becoming alienated from the workings of nature; when man could no longer observe the solid, material processes of life, and identify with them; he had to invent God in order to explain how life happened and why death happened.

“Now just a minute,” snapped Jesus.

“Maybe I should run along,” said Tarzan, sticking his harmonica into the myrrh-stained Arab silk that girded his loins.

“No,” said Jesus. “If you have more to say, then out with it. Where does Pan fit into this blasphemy? And I?”

“If you’re sure you want to hear it. Confidentially, you look a bit under the weather to me, pal. You could use a pound of steak and some fries.”

“Do continue,” sputtered Jesus through his drool.

“The point is, J.C., we had a unified outlook on life. We even figured out, in our funky way, how the sun and moon and stars fit into the process. We didn’t draw distinctions between the generative activity of seeds and the procreative cycles of animals. We observed that growth and change were essential to everything in life, and since we dug life, when it came time to satisfy our inner needs we naturally enough based our religion on the transformations of nature. We were direct about it. Went right to the source. The power to grow and transform was not attributed to abstract spirits–to a magnified ego extension in the sky–but was present in the fecundity of nature. We worshiped the reproductive organs of plants and animals. ‘Cause that’s where the life force lies.”

Jesus kicked a pebble with the worn toe of his sandal. “I’ve heard of the phallic and vegetation cults,” he said. “Not very sophisticated. My father expects more of man than a primitive adoration of his carnal natures. He must rise above…”

“Rise to what, Jesus? To abstractions? And alienation? Your scroll there, your book of Genesis, says that in the beginning was the Word. The simplest savage could see that in the beginning was the orgasm. Life is reproduced from life, while resurrection–the regeneration of seeds, the return in the spring of the leaves that fell in the autumn–is of matter, not of spirit. Unsophisticated? Maybe it’s unsophisticated to venerate mountains and regard rivers as sacred, but as long as man thinks of his natural environment as holy, then he’s gonna respect it and not sell it out or foul it up. Unsophisticated? Hell, it’s going to take science a couple of thousand more years to determine that life originated when a cupful of seawater containing molecules of ammonia was trapped in a pocket in a shore rock where it was abnormally heated by ultraviolet light from the sun. But we pagans have always sensed that man’s roots were inorganic. That’s why we had respect even for stones.”

Jesus looked up sheepishly from the pebbles he’d been kicking. “But you hadn’t been saved,” he protested.

“Didn’t need to be,” said Tarzan. “Wasn’t of any use to us.”

“Well, in the old days the female archetype was the central religious figure. Man had the power of creation, but it was in women that we observed the unfolding of the life cycle: reproduction, death and rebirth. So we celebrated the sensuality of God the Mother. Agriculture is umbilically tied to the Great Belly. Whereas the domestication of animals, a later pursuit, is more of a phallic activity–it was a step away from God the Mother and a step toward God the Father. But a harmonious balance was maintained. And Pan personified that balance. He kept things unified, him with his beautiful music and his long red erection.

“But when you came along, well, the way I hear it is your coming represented the triumph of God the Father over God the Mother, victory of the Judaic God of spirit over the old God in flesh. Your birth-cry signaled the end of paganism, and the final separation of man from nature. From now on, culture will dominate nature, the phallus will dominate the womb, permanence will dominate change, and the fear of death will dominate everything.

“Pardon me, Jesus, ’cause I know you’re a courageous and loving soul. You mean well. But from where I swing, it looks like two thousand miles of bad road.”

Jesus looked to the heavens for guidance, but he saw only the angel, hangin in front of their parley the way a sign hangs in front of a TV repair shop. “Then that explains why you have withdrawn into your private nirvana,” he said at last.

“You might say that,” said Tarzan, standing up to stretch. “Why beat my head against a penis abstraction? And you, what are you doing out here in this snaky wilderness, frying your butt on a hot rock?”

“I’m preparing myself for my mission.”

“Which is…?”

“To change the world.”

Tarzan slapped his side so hard he bent his harmonica. “The world is perpetually changing,” he roared. “It doesn’t do much else but change. It changes from season to season, from night to day, from ice to tropics. It changes from a pocketful of cosmic dust to the complicated ball of goof and glory it is today. It’s changing every celestial second with no help whatsoever. Why do you want to stick your nose into it?”

“The peoples of the world have become wicked and evil,” Jesus said gravely. “I believe, in all modesty, that I can eradicate their evil.”

“Evil is what makes good possible,” said Tarzan, hoping that he didn’t sound too trite. “Good and evil have to coexist in order for the world to survive. The peoples haven’t become evil, they’ve lost their balance and become confused about what they really are.”

He jumped on the back of his goat and gave it a smack. “I’m afraid, Jesus baby, that you’re gonna confuse them all the more.”

The jungle yogi started to ride off, but Jesus leaped up and grabbed the goat by its tail. “Whoa, no, whoa,” he called in his rich olive-green baritone. The animal stopped and Tarzan looked Jesus in the eye, but Jesus had difficulty articulating the activity in his brain. “If you think carnally then you are carnal, but if you think spiritually then you are spirit.” He just blurted it out, but it didn’t sound too bad, and the odor of the goat obscured any desire he might have had to develop his idea more comprehensively.

Tarzan rattled the nanny’s rib cage with his heels and she bolted out of the prophet’s grasp. “Any law against thinking both ways?” he asked. He began to ride toward the south.

“You’re either for me or against me,” yelled Jesus.

“Well, adios then. I’ve got to beat it on back to the Congo. Jane promised to lay out a luau when I returned. Been gone two weeks now, a-riding over the good earth and a-playing for anybody who’d listen. Bet Jane’s as horny as a box of rabbits. Git along, nanny!”

The goat galloped off in comic-strip puffs of dust. Jesus returned to his rock and shooed an entwined pair of butterflies off the Law. His heart felt like the stage on which some Greeks had acted a messy tragedy. So occupied was he with swabbing the boards that several minutes passed before he thought to look after the angel. When his eyes found it, it was flapping erratically in the high, dry air, first soaring after the disappearing strains of Tarzan’s harmonica and then returning to hover over Jesus, back and forth, again and again, as if it did not wish the two to part–as if it did not know whom to follow.