Edwardian-social-issue-of-the-week: mass hysteria

“Supernatural” crime: Spring Heeled Jack attacks!

Cards on the table; we here at The Ghost Racket are massive, long-term Spring Heeled Jack fans and we’ve been eagerly anticipating Houdini and Doyle’s take on London’s “leaping ghost” for many months. How does it compare to the frustrating SHJ storyline in the 2015 Jekyll and Hyde series? Read on …

Episode 4 opens, curiously, with a newsboy hawking the latest London buzz; automotive omnibuses are soon to replace the good old horse-drawn variety. Automobile magnate Barrett Underhill should be on top of the world, but instead he’s perturbed by a sinister note quoting Moby Dick, which is slipped under the door of his 7th-floor hotel room:

From Hell’s heart, I stab at thee!

Later that night, Underhill is roused by strange flutterings and scratchings at his window. Investigating, he opens the window and gazes out over the London roofscape – but then, just as he glances upward, a demonic, bat-like figure hurls itself at him from above, sending him plummeting to his death!

The next morning Constable Stratton summons Houdini and Doyle, and they learn that the hotel doorman spotted an uncanny winged figure leaping or flying from the roof moments after Underhill fell. Houdini, scoffing at the suggestion that a demon might have been to blame, leaps to the conclusion that it was simple misadventure; the startled doorman, Houdini suggests, mistakenly associated the coincidental overhead flight of a large bird with the man’s accidental, or perhaps suicidal, death. Stratton and Doyle aren’t so sure – after all, Underhill was just about to make a great deal of money from the automotive omnibus deal, and had also just received an overtly threatening, anonymous note.

Stratton, meanwhile, receives a mysterious telegram and temporarily excuses herself from the case, claiming illness.

Investigating Underhill’s business rivals leads Houdini and Doyle straight into a confrontation with a Mr. Tuttle, the owner of London’s largest horse-drawn bus company. Tuttle is a surly man who seems to have had both motive and method for murder. Doyle, however, pursues the supernatural angle and notes that the hotel doorman’s description, and the circumstances of Underhill’s death, are highly reminiscent of the legend of Spring Heeled Jack. Just then the two amateur detectives encounter Lyman Biggs, a cheerily verbose tabloid newspaper reporter who decides the “leaping demon” angle is far too good to pass up.

Shortly thereafter, a slumlord is pursued through the back alleys by an agile, shadowy, blue-fire-breathing phantom. The landlord’s body is found the next morning, gruesomely impaled on the railings of a high fence. Then Jack strikes again, smashing through the window of a wealthy Russian woman’s apartment and slashing at her with his claws before leaping off into the night.

Within days, London is paralysed by the fear that Spring Heeled Jack has returned. Doyle notes darkly that his reappearance has always betokened some great disaster, while Houdini takes the opportunity to demonstrate how easily mass hysteria can be conjured by briefly convincing a roomful of people that they’re endangered by an invisible gas.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s family is swept up in the general Spring Heeled Jack panic, as his young son Kingsley becomes tearfully convinced that Jack is stalking him; Doyle seems unable to comfort the boy beyond telling him to keep a stiff upper lip.

Houdini, Doyle and Stratton are eventually able to eliminate Mr. Tuttle as a suspect – he did write the threatening note, but cannot have committed the Spring Heeled Jack attacks. Pursuing a lead offered by the Russian woman, the trail then leads to a circus acrobat, Vladimir Palinov, who was both a jilted suitor of the woman’s and a recently evicted tenant of the landlord’s, but who seems to have had no connection to Underhill the automobile magnate.

That night, Lyman Biggs, the journalist, is confronted by Spring Heeled Jack, who drops from the shadows above; but Biggs quickly recovers his composure and berates the costumed figure before him for “nearly giving the game away”. “Jack” then pulls off his mask to reveal the face of Harry Houdini; as it turns out, Palinov the acrobat confessed that Biggs had hired him to impersonate Spring Heeled Jack in order to “goose the story” and sell more papers. Biggs himself, therefore, has accidentally just admitted to orchestrating the plot to the disguised Houdini.

Later, however, while being interviewed in prison, Biggs claims that the slumlord’s death was a tragic accident. Palinov had only been trying to scare him, and the panicked victim had slipped and impaled himself on the railings while trying to escape. Biggs also insists that he had nothing to do with the attack on Barrett Underhill, and, in fact, that he had never even heard of Spring Heeled Jack until he overheard Doyle describing the demon to Houdini. At that point, he conceived the plan to bring the legend to life, so as to profit by fear-mongering through his newspaper stories.

In the final shot, a mysterious, dark figure is watching Houdini and Doyle from the rooftops …

Observations:

- This is the first episode in which we start to get a real feel for Houdini, Doyle and Stratton as characters of significant depth. Doyle’s “stiff upper lip” reserve, which has sometimes registered as rather wooden, is now starting to make more sense; he’s terrified that he’s going to lose his comatose wife Touie forever, and doesn’t know how to deal with that fear (or with his children’s fears).

There’s a very strong scene in which Houdini and Doyle debate the nature of fear and the best way to deal with it; Houdini, fulfilling his role as the brasher, more outwardly emotional of the two, urges Arthur to admit his terror, telling him that this is the only way it will lose its power over him. Arthur is then, in a rather touching interlude, able to tell his son that it’s all right to be afraid.

- The Adelaide Stratton character is still a bit of an enigma; she’s often almost as reserved as Doyle, but in this episode we at least learn that she is (or has been) married. The mysteries of her past relationship(s) seem to be being set up as a major through-line for the series. Despite excusing herself from the investigation early on, she does have a bit more to do in this episode than previously.

- The pattern develops apace; Houdini consistently jumps to the wrong conclusion straight off the bat, but he’s also consistently right about the ultimate solution being non-supernatural. Doyle’s more cautious approach – as befits a trained physician and the creator of Sherlock Holmes – admits more possibilities, though he’s very apt to get side-tracked looking for paranormal explanations where none actually exist. Stratton can see both sides and basically serves as the referee, though again, it would be nice to see her display more of an independent set of personality traits and motivations.

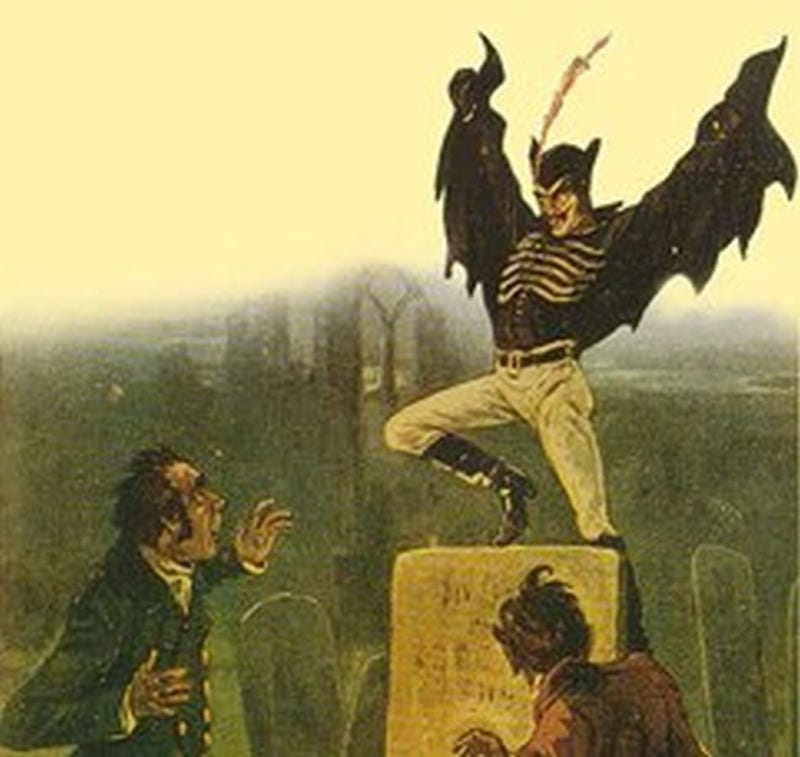

- After the disappointment of the Jekyll and Hyde treatment, in which Spring Heeled Jack was presented as a rather hapless, ineffectual character, it’s wonderful to see justice done to Jack in a fairly major TV series. His appearances are all suitably mysterious and dramatic and the writer obviously did his homework regarding the actual folklore. Some of the “historical sketches” Doyle produces to explain the legend to Houdini are closely inspired by actual 19th century SHJ-related art, although one sketch is, rather cheekily, based on the monster from the 1957 movie Curse of the Demon!

Jack’s acrobatics are also very pleasingly handled – it’s a good bet that a parkour-trained stuntman executed his street gymnastics of vaulting and side-flipping over walls, etc. Dynamic stuff and, again, just what we were hoping for in watching Spring Heeled Jack in action.

- It’s implied that the “great disaster” foreshadowed by Spring Heeled Jack’s appareance in early Edwardian London is the pollution that will follow once automobiles fully replace horse-drawn vehicles. It’s also implied, though, that virtually any two events can be tied together via the confusion of correlation with causation …

RATING:

‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ ‽ _

Nine ibangs out of ten for our favourite episode so far! Plenty of action and mystery, some welcome character development and the whole thing moves along at a cracking pace.