The new TV series Houdini and Doyle teams these two very famous figures, together with pioneering female police constable Adelaide Stratton, investigating apparently supernatural mysteries in early Edwardian London.

Obviously, the series is a work of fiction inspired by some historically real characters and situations, with a lot of creative license applied. For example, whereas the real Harry Houdini and Arthur Conan Doyle were, in fact, friends for a few years, that friendship actually occurred during the early 1920s rather than circa 1901, and of course the premise of their working together to solve “supernatural” crimes is entirely fictional.

It’s true, however, that Houdini and Doyle did investigate paranormal claims, individually and from very different perspectives. Both men had a long-standing interest in the nascent religion of Spiritualism – the purported practice of communicating with the spirits of the dead.

Doyle’s interest was that of a devout believer in the supernatural who was concerned about the widespread practice of “spirit fraud” or “playing the ghost racket” – the con-game of using magic tricks and psychological manipulation to hoax “suckers” into paying for fake psychic communication with the dearly departed. From Doyle’s point of view, this represented an intolerable perversion of a noble spiritual practice, and he conducted a number of investigations into the practices of spirit mediums to try to determine if they were being honest about their abilities.

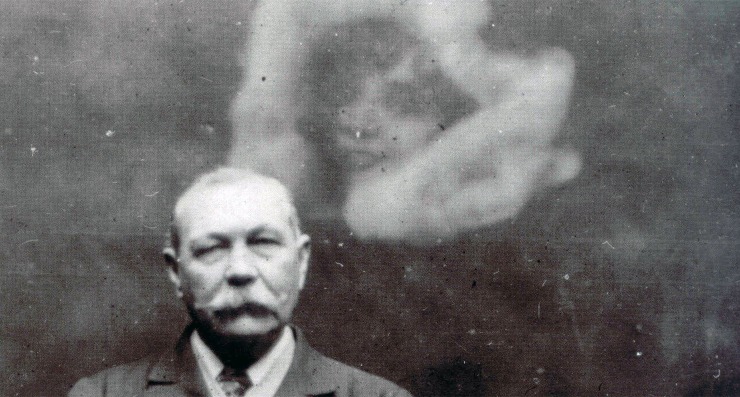

Doyle was not, however, experienced in the techniques of deception, relying instead upon his powers of observation and deduction – which were rather less than those of Sherlock Holmes – and his sense of an individual’s character. Although he believed in the scientific method, he wanted and expected it to prove that paranormal events did, in fact, take place. As such, he was frequently deceived by ghost racketeers and even by much simpler and more innocent hoaxes, such as the famous Cottingley fairy incident.

In 1922 Doyle led a defection of members from the Society for Psychical Research, on the grounds that the Society had become too skeptical. His enthusiastic endorsement of a number of people and events later proved to have been fraudulent did no lasting good to his reputation. His biographers point out, however, that – although Doyle himself denied it – his passion for the subject of Spiritualism may well have been fired by the fact that he lost seven family members shortly after the end of the First World War.

Harry Houdini, for his part, professed a willingness and even an eagerness to believe in spirit communication, but also possessed a lifetime’s training in methods of artful misdirection, concealment and other forms of trickery. He attended numerous seances, but in each case he quickly saw through the magic tricks being employed.

Like Doyle, Houdini became very angry when he saw the naive trust of seance attendees – many of whom were recently bereaved – being taken advantage of by ghost racketeers, particularly after his mother died in 1913. Unlike Doyle, he saw evidence of spirit fraud everywhere, and so he began a crusade against the fraudsters. Houdini quickly gained notoriety among the subculture of ghost racketeers and took to attending their seances in disguise before loudly exposing their tricks.

Later, he would engage a team of private detectives, referred to as his “secret service”, whose job was to travel the USA gathering evidence of spirit fraud, which would be passed on to Houdini for his exposés. One of his most trusted and experienced detectives was Rose Mackenberg, who went on to become among the most prominent “ghost breakers” of the 20th century.

Although Houdini and Doyle liked and admired each other, exchanging frequent letters and even vacationing together, they never agreed on the “spiritualist question”. Doyle was actually convinced that Houdini was among the greatest “physical mediums” in the world, mistaking Houdini’s skill at magic illusions for evidence of actual psychic powers. Houdini, adhering to the magician’s code, was unable to explain to his friend exactly how the tricks were really done, though he assured Sir Arthur that they were performed by strictly natural means.

Matters came to a head when Lady Doyle – herself a “psychographic medium”, meaning that she produced “automatic writing” believed to be dictated by a spirit guide – conducted a seance in which she attempted to channel the words of Houdini’s much-beloved mother. Houdini maintained a polite facade, but inwardly he was unconvinced; Lady Doyle’s automatic writings were in English, a language his late mother had barely spoken, and were headed with a cross, a symbol unlikely to have been used by the devoutly Jewish Cecelia Weiss. Also, the day of the seance happened to have been his mother’s birthday, but that fact was not mentioned in the writing.

Although it’s sometimes assumed that Lady Doyle was deliberately attempting to con Houdini, that’s not necessarily the case; given the right circumstances of belief and emotional investment, it’s entirely possible that she genuinely believed that her automatic writing was being dictated by a discarnate spirit. Houdini did not believe, and exited the situation as gracefully as he could, not wishing to offend his friends.

After Sir Arthur publicly (and, probably, sincerely) proclaimed that Houdini had been converted to Spiritualism by this seance, however, Houdini had no choice but to vehemently dispute that claim. Their former friendship quickly turned to bitter rancour and they waged a public relations feud via their newspaper articles, lectures and investigations, each man becoming, in effect, the champion of his own side. Sir Arthur argued vehemently in favour of spiritualism, while Houdini countered with exposé after exposé of prominent mediums, right up until his untimely death in October of 1926.

Doyle, who passed away four years later, never lost his belief in Spiritualism and also continued to believe that Houdini had been a master medium in denial.