One of the most curious examples of late-19th/early 20th century “trance mediumship” is that of Catherine-Elise Muller, a young French woman who believed herself to be in regular psychic contact with the inhabitants of the planet Mars.

This was the heyday of spiritualism; the purported practice of contact with “the world beyond” by practitioners known as mediums. Typically, a medium would conduct a ritualistic sitting (or seance) for a small group in a darkened room, entering a trance state that was supposed to allow a discarnate “spirit guide” to communicate through them. This entity would then answer questions posed by the group, via various means such as “automatic writing”, after which the medium would return from the trance state, often professing no memory of what their spirit guide had said.

Miss Muller’s professed spirit guides had previously included an ancient Indian princess, the sorcerer Cagliostro and the famed author Victor Hugo. During the 1890s, however, she began to channel what she believed to be the voice of Esenale, a “translator” and resident of Mars. Esenale’s communiques, which included both speech and an intricate form of sign language, eventually included detailed descriptions of Martian culture, technology, flora and fauna. The latter included the vaguely Asiatic Martian humanoids and the troll-like inhabitants of “Ultra-Mars” as well as semi-sentient dog-like creatures whose heads “resembled cabbages” and who were capable of running errands and even taking dictation.

Over a number of seances, Miss Muller also produced a glossary and alphabet of the Martian language. The phrase “Dode ne haudan te meche metiche Astane ke de me veche“, for example, meant “This is the house of the great man Astane, whom thou hast seen,” whereas Martian script looked like this:

Ultra-Martian, on the other hand, was a separate language entirely, with its own alphabet.

Skeptics, including the psychologist Théodore Flournoy who worked closely with Muller over a period of about five years, noted that her Martian languages were structurally almost identical to her native French. Flournoy presented his findings in a book titled From India to the Planet Mars, which became a popular curiosity amidst the prevailing cultural debates on spiritualism.

It should be noted that while Flournoy did not believe that Miss Muller was actually communicating with Martians, nor did he think that she was deliberately inventing her Martian visions; rather, he opined that she had a singular gift for unconsciously compartmentalizing her own creative imagination. Flournoy expressed admiration for his subject’s creativity and also protected her identity by giving her the pseudonym “Helene Smith”. The medium herself was not pleased with his book, which presented her as a psychological case study in glossolalia rather than as a psychic; however, From India to the Planet Mars made her reputation and she continued to use the Helene Smith pseudonym professionally.

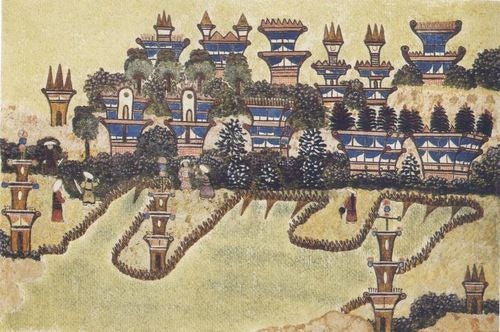

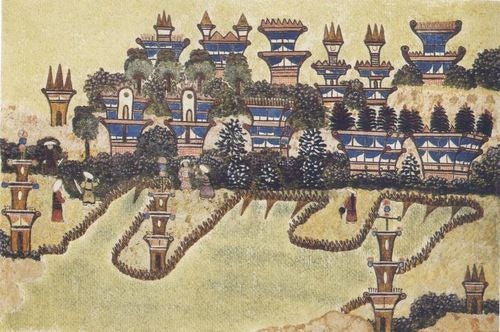

In the years that followed, she accepted the generous patronage of an American spiritualist and developed a form of Christian spiritualism with extraterrestrial elements. She also turned increasingly towards “automatic art”, producing intricate paintings of Martian landscapes and architecture as well as images of Jesus Christ. These paintings, which would probably be classified as “outsider art” today, were embraced particularly by the Surrealist movement during the first decades of the 20th century.

See Daniel Rosenburg’s essay, Speaking Martian, for a more complete examination of this peculiar case.

Note – an earlier version of the above article originally appeared on the Past Tense blog. It is re-used here by permission.

Rose Mackenberg was among the most prolific and experienced “spook busters” of the 20th century, having learned at the feet of Harry Houdini himself as a member of Houdini’s “secret service”. Disguise was a necessary weapon in her arsenal and her first stop in any new town was the local department store; there she would spend several hours making notes on the clothing of various “types” of women whom she might be required to impersonate in infiltrating fraudulent seances.

Rose Mackenberg was among the most prolific and experienced “spook busters” of the 20th century, having learned at the feet of Harry Houdini himself as a member of Houdini’s “secret service”. Disguise was a necessary weapon in her arsenal and her first stop in any new town was the local department store; there she would spend several hours making notes on the clothing of various “types” of women whom she might be required to impersonate in infiltrating fraudulent seances.